I was recently in Bihar where I visited the Sita Ram Upadhyaya Museum in Buxar with the purpose of studying early fifth-century terracotta temple panels and architectural elements excavated from a large archaeological mound, 10 metres in height, in the nearby village of Chausā in 2014, for an article I am working on. This mound is perhaps most famous locally for being the site of the 1539 battle of Chausā in which the Afghan ruler, Sher Shah Suri, defeated the Mughal Emperor Humayun. Chausā has been known to scholars of Indology and art history since 1931 due to the important hoard of 18 early Jain bronzes that were unearthed in a field here. Some of these bronzes are distinctly Gupta in style. Chausā is also known for being the place of origin of a terracotta panel depicting a Rāmāyaṇa scene housed in the old Patna Museum (possibly transferred by now to the new Bihar Museum). This panel belongs to the same lost temple as the panels excavated decades later.

In this post I am going to discuss a single panel from the Chausā collection which might constitute the earliest extant temple image of the birth of Śakuntalā. This story features in chapters 71–72 of the Sambhava Parva of the Ādiparvan (first part) of the Mahābhārata. It tells of how Indra, king of the gods, was becoming perturbed at the increasing power of king-turned-sage, Viśvāmitra, who was performing advanced austerities. Indra, keen to protect his throne, sent the most beautiful of the asparas‘ (celestial nymphs), Menakā, to tempt Viśvāmitra away from his penances. Menakā, aware and afraid of the great power of Viśvāmitra, asks Indra to send the gods of wind and love with her to ensure her success. When Menakā arrives at the āśrama of the sage, the wind god causes a great gust to blow away her clothes which she then shyly attempts to retrieve. Having witnessed this mishap, Viśvāmitra falls in love there and then and invites Menakā to live with him. They spend many happy years together frolicking; years that feel like no more than a day.

When Menakā becomes pregnant, she leaves the sage, her task having been completed. She gives birth to a girl on the bank of a river in the Himalayas and then returns to the heavens leaving the infant behind. The vulnerable baby girl is protected by forest birds and so receives the name Śakuntalā (the one protected by birds). She is discovered by Sage Kaṇva who becomes her foster father.

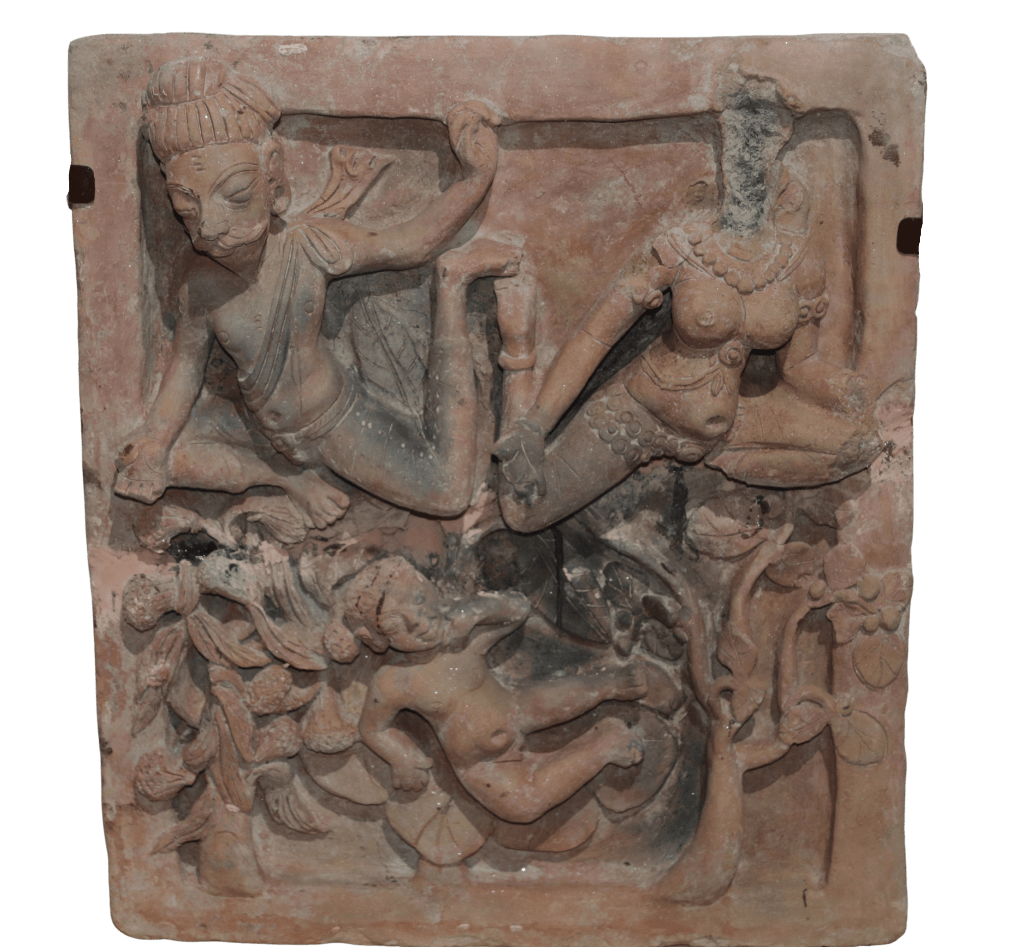

We turn now to the Chausā panel and its exuberant iconography.

In the top register we observe Viśvāmitra and Menakā departing at speed in opposite directions, conveying the end of their relationship and the abandonment of their daughter Śakuntalā, who is depicted in the lower register lying on lotus pads in a forest glade. In the upper midpoint of the panel, a foot each of the erstwhile couple touch, perhaps an intentional reminder of the love and intimacy they shared. On the lower left of the panel is an Ashoka tree (saraca asoca), while to the right is a tree that could be a young Peepal (ficus religiosa) or a type of ficus palmata. The leaves of a palm tree are visible behind the fleeing figures. Despite being deserted by her parents, Śakuntalā has a smiling, content countenance.

Viśvāmitra has wonderfully characterful appearance. His matted hair is worn in a top knot and he sports a thick moustache and a suave pointed beard. He has tripuṇḍra (three lines, usually made from sacred ash) smeared on both his head and chest, marking him out as a devotee of Śiva.

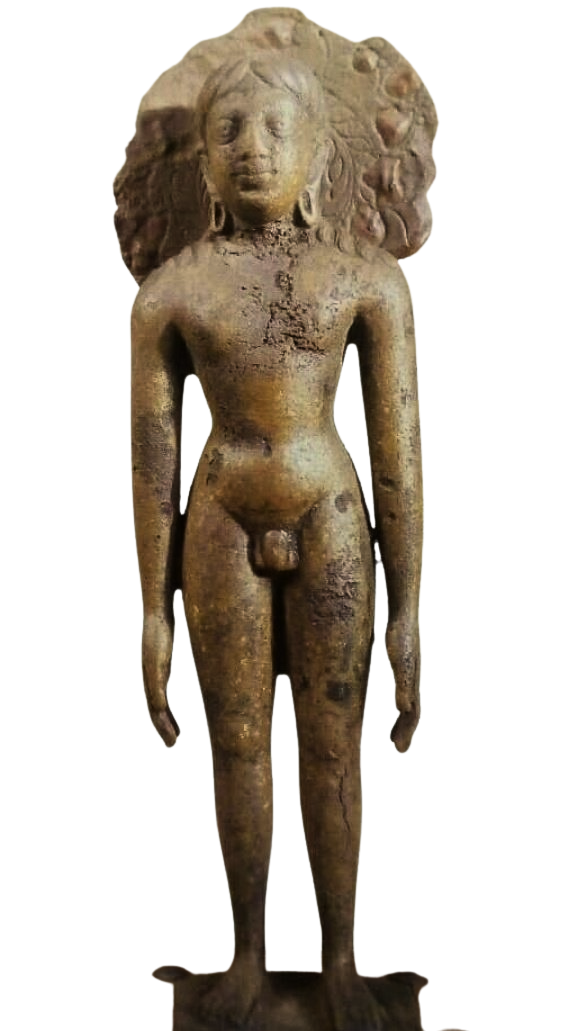

Menakā’s face is sadly lost so I include here an image of one of the graceful terracotta women of Chausā to give an approximate indication of what she might have looked like.

The panel imagery does not precisely align with the Mahābhārata telling. Most significantly, both Viśvāmitra and Menakā appear to be airborne in the panel. For all his powers, there is, to the best of my knowledge, no surviving textual account of Viśvāmitra having the ability to fly without the aid of a vehicle. Secondly, in the Mahābhārata, the couple separate before the birth of Śakuntalā. And finally, there are no birds represented in this panel – perhaps they would have featured in a lost sequential panel. There are various tellings of the relationship between Viśvāmitra and Menakā in ancient and early texts including one in the Rāmāyaṇa, but this and many others do not include the birth of Śakuntalā. The panel then, might constitute a unique take on the myth, or might illustrate an oral or textual telling that has not survived in another medium.

There are possible traces of red and white paint on the panel but this would need to be confirmed via scientific examination.